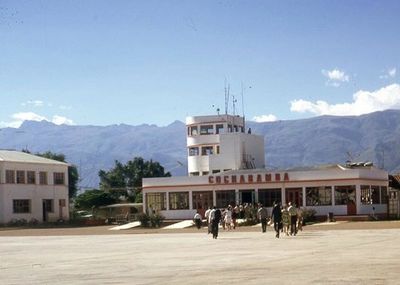

Arriving in Cochabamba, Bolivia

April 1991

At some point during our overnight flight, with the passengers in the cabin mostly asleep and the lights dimmed to near darkness, we crossed the line of the planet’s hidden waist and slid from the north to the south, from spring to autumn, and toward the lives in Bolivia that we had plotted out but not yet begun.

Our first landing in Bolivia was brief, a stopover in the Santa Cruz airport where we could feel the tropical air as we descended the metal stairs to the tarmac. After a short wait a second Lloyds Aero Boliviano flight carried us forty-five minutes onward to Cochabamba. Even after landing we remained at eight thousand feet higher than the sea. The morning air felt thin and crisp and the sky was an uninterrupted blue.

One of the first things we noticed as we walked from the plane toward the terminal was the young soldiers with rifles slung over their shoulders. Their heads were half-hidden by white metal helmets that looked like huge overturned soup bowls. The second thing we noticed was the terminal itself, a giant antiquated Quonset hut of a building with an arched metal roof that might have been new in the 1930s. We had not only swapped hemispheres but in various ways had traveled back in time as well.

The recovery of our dirty blue backpacks involved some complicated communications with one of the handful of old men who grabbed luggage off the slow wooden conveyor belt in exchange for a few coins. This was followed by a careful look over from another pair of men who studied our white luggage tags to be sure we hadn’t traveled all the way from the U.S. to steal someone else’s bags.

As it turned out, we had given the staff at Amistad wrong information about when our flight was due and had arrived two hours early. So we set ourselves up to wait beside the miniature airport parking lot (room for maybe two dozen cars) and took advantage of an unplanned moment of reflection before everything new began.

At one end of the lot a threesome of taxis—a matching set of beat-up old Ford Falcons from the early 1960s—sat waiting in vain for passengers. Somewhere in the thirty years since these small cars had come off a Detroit assembly line, they had also migrated across the world to this quiet Andean valley. Despite repeated invitations from the drivers, we assured them that we really didn’t need to go anywhere.

We parked ourselves on an old wooden bench, alternating between a spot in the sun that quickly became fiercely hot and a spot in the shade of a purple-blossomed jacaranda tree that still held the cold of the night before. I had grown up with a tree just like it in my front yard in Whittier.

An hour and a half later, an aging red Toyota taxi drove up. In the passenger seat sat a smiling woman in her late 30s with black hair, giant black plastic glasses, and a small bouquet of flowers in her arms. This was Carmen Sanchez, Amistad’s secretary. It couldn’t have been too hard for her to figure out that the two young gringos on a bench were Lynn and Jim. After a round of hugs and warm greetings, her driver, a young man named Hilarion, tossed our packs in the trunk on top of a dirty spare tire. Soon we were in the back seat being carried up a steep cobblestoned road to the hillside on the northern edge of the city and the house that would be our home for a year.

Copyright © 2025 Jim Shultz "The Writer" - All Rights Reserved.