Introduction

When does a journey begin? It’s not when you board the bus, or the train, or the plane. It’s not when you pack your bags. It isn’t when you start to plan your itinerary or buy your tickets. The journey begins when the idea of it dances as an inspiration into the outer edges of your mind and the mystery of the universe plants it there and it remains.

Many people think about moving for a time to another country. They are drawn to the idea of having an adventure, of doing something more than just vacationing in a place. They want to know a different culture

from theirs from the inside. A smaller number of people actually succeed in doing this—life has a tendency to get in the way.

For those who do make such a journey, often it’s just for a short while, a few months or a year. They go to places not so different from where they left. New York is swapped for London. A small town in California is swapped for a small town in France. The language may be new and the local bread might come in another shape, but still the differences can be overshadowed by the similarities. Rich countries in one place tend to be a lot like rich countries in another.

Then there is Bolivia.

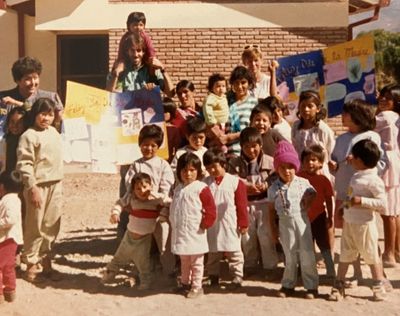

In February 1991, my wife, Lynn and I left behind our jobs, our apartment, our cat, and our friends in San Francisco to spend the first year of our marriage as volunteers in an orphanage in a place called Cochabamba. We passed one full orbit of the Earth around the Sun living in a very different place and spending our days in a very different way than we had as young professionals in California. Our plan was that, afterwards, we would come home and do the expected things—look for new jobs, buy a house if we could, have children, and raise a family in the Bay Area.

That was the plan.

Life however, took us down a very different road. We ended up returning to Bolivia and living for two decades there. We adopted three Bolivian children. We made a rich life in a new country far from home. We were

altered in ways that we still do not fully understand.

I wrote a good deal about Bolivia during our years there—articles about its political uprisings, a popular blog about its events and quirks, and a book about its revolutionary challenges to globalization. But I did not have a plan to write about our lives there. That changed toward the end when I began to see that our time in Bolivia was going to come to a close. I read something once, that if you are a writer you have not fully experienced a thing until you have written about it. I did not want to leave Bolivia without fully experiencing it.

It is a very strange experience writing about your life and your family. My inner doubts did a lot of screaming at me as I wrote: Who do you think will actually be interested in this? Is this a fair thing to do to your family, making your shared story a public one? How can you trust your memories? Are you out of your mind?

I managed to keep those voices at bay long enough to finish the writing. Bolivia is known for its wonderful weavings, and in a weaving the hands of the maker interlace two sets of threads. The lengthwise threads of

colored yarn are known as the ‘warp’ and are held stationary by the top and bottom edges of the loom. Its dance partner is the ‘weft,’ the strings that are pulled from one side to the other, over and under the others. The result of that dance between strings of thread can be some of the most beautiful work you will ever see.

For nineteen years Bolivia was our warp, a place of extraordinary people, mystical geography, and deep culture. We turned ourselves into the weft, weaving through another country’s life until it merged with ours and we became something new.

That life and this book are a weaving about many things. It is about working with orphaned children. It is about accidentally falling into the center of a South American political revolution. It is about the three children who became our family and the mountains and fields that became our home. It is about three dogs, indigenous rituals, traveling on dangerous roads, a guy searching for the lost city of Atlantis, fishing for piranha, getting stuck in a landslide, visiting a friend unjustly jailed, and getting bombed with water as we walked down the street during Carnaval.

But it is also about the quieter rituals of daily life in a very different place—walking children to school, negotiating the price of tomatoes in the market, reading to neighborhood children, navigating adolescence, and all of the other things that are part of every family’s life, but in our case in a culture not our own.

We know quite well that we have been deeply fortunate to be able to have this adventure. Few people in the world have such an enormous privilege to move freely to another place and make a good life there. Bolivia

welcomed us. Our own country, the United States, is not so hospitable to foreigners, especially as I write this. Bolivians trying to make the trip in the other direction are treated to a huge non-refundable visa application

fee, an unfriendly interview at the U.S. Embassy, and more often than not, a rejection. Migrants who walk to our borders face far worse. When you find yourself in a position of such privilege it seems imperative to use it to

offer acts of service and friendship and to make a commitment to work for deeper justice. We did our best and sometimes we were better at that than others.

Some of you who find this book in your hands may be thinking about your own possible journey beyond borders. If that is the case, I hope you find some inspiration here to do it. There are all kinds of atypical journeys that one can make in life and they are not all about travel. The best ones, I think, are all about this one thing: telling conformity ‘no thank you’ and finding your own way. A handcrafted life can be much more than one of the many pre-packaged versions you can buy prepared for you off the shelf. This has been our handcrafted life. Best of luck with yours.

Jim Shultz

Lockport, New York

Autumn 2019

Copyright © 2025 Jim Shultz "The Writer" - All Rights Reserved.